Fantasy Map Making Geography 101

When creating Worldographer and its map generation algorithm, we learned a lot about planet geography. Whether you’re using Worldographer’s generator or you’re going to make your own fantasy map (regardless of tool) the following information should be a great resource. Note: We also made a video based on this article. Watch it here.

Planet Shape & Size

There are a number of possible world shapes in fantasy & science fiction: Ringworld & Hollow Earth are two prominent non-sphere examples. Other ideas are die-shaped worlds (d4, d6, d8, d10, d12, & d20, and probably others), a Möbius strip, and a flat map–which would make mapping it accurately easier.

But for our purposes, we’re going to focus of sphere shaped worlds. For size, keep in mind the circumference of the earth at the equator is 24,901 miles. You can go smaller or larger, depending on how big of a canvas you want.

Area to Develop

However, you’re likely only going to do a detailed map of a smaller area such as one continent or part of a continent. Unless you’ve got oodles of ideas that can fill a whole world ready to go (great if you do!) you can focus on just the one kingdom where the PCs will start and maybe a couple adjacent kingdoms or nations.

There’s no real harm in putting down the broad brush strokes for other areas of the map. The major geographical features and largest cities will be enough for your players to pick for character backgrounds. (If they don’t want to be from the starting area.)

Coastlines

Worldographer starts its world generation by sticking down several land masses of varying sizes. Where they overlap is where the first hills and mountains will be placed. This sort-of simulates plate tectonics in a very basic way. A land percentage setting in Worldographer determines how many land masses it places. And these land masses determine our initial coastlines.

If you’re using another tool (or even paper) you can easily do the same to create your coastlines, mountains, and hills. Just keep adding land and refine it.

Landforms

Next when making a fantasy map you’re going to want to add some more landforms to fill out the world.

- Mountains: Usually at least partly surrounded by hills or other elevated/rugged terrain. In addition to forming where crumpling plate tectonics overlap, volcanoes form mountains. They often run parallel to coasts because of plate tectonics. However, volcanoes tend to form mountains in clumps (to relieve intense pressure with several “spigots”) and lines (as plates move over a “spigot” over time).

- Foothills: These surround mountains and are usually more rugged than other hills, depending on how much time erosion has had to work.

- Rolling Hills & Tablelands: These are hills that are more eroded away and possibly now cultivated. They can also be highlands, shields, bulges, etc.

- Depressions: Areas lower than sea level that you can sprinkle across your map. These may form swamps, marshes, seasonal lakes, inland seas, and salt flats.

- Gorges: Steep passes & valleys formed by riven canyons.

- Escarpments: Sudden changes in elevation such as the edge of a plateau.

Climate

After you’ve thought through your coastlines, mountains, and other landforms it is time to think about climate. Is your planet earth-like? More arid or humid? Colder or hotter?

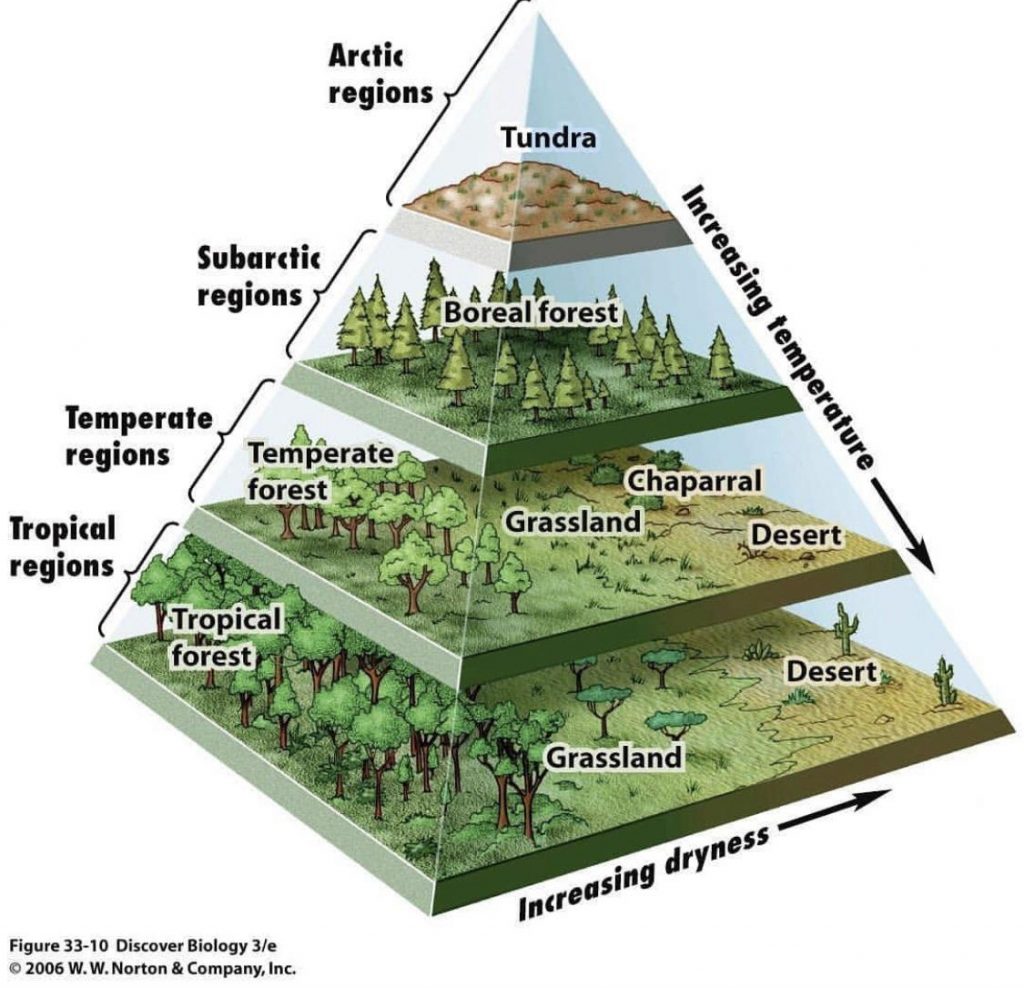

If you’re making an Earth-like world, then you’ll have an arctic climate at the poles, then subarctic, followed by temperate, next subtropical, and finally tropical near the equator. Of course for a hotter world, drop the first, second, or even third of those. Perhaps also make the area near the equator nearly inhospitable without being a special creature, or using magic or devices. On the other hand, for a colder world drop the climate mentioned later in the sentence above. And likewise consider making the area near the poles inhospitable.

Elevation will also affect the climate of an area. In a tropical region, high mountains can still be snow-covered year round. And as you progress down the slopes of those tropical mountains you may have areas of temperate or sub-tropical climate.

Wind

After climate, think of wind patterns and how wind will bring moisture or dry air to a region. You may want to mark your map with red and blue arrows to note this. As a quick meteorology lesson, wind is developed by high and low pressure cells over large bodies of water as well as large landmasses to a lesser degree. In the northern hemisphere on Earth these rotate clockwise, but in the southern hemisphere they go counter clockwise.

Wind does blow over most mountain ranges, but as it does it loses moisture. So you’ll have one side facing where the wind is coming from with vegetation, and less vegetation on the other side of the mountain range. Especially high mountain ranges can divert the wind.

Inland Seas, Lakes, & Rivers

As mentioned above, inland seas form in low areas often below sea level. Rains and rivers flowing into the sea bring water, but there is no lower land nearby for a river to flow out to the sea. When at least some of the water evaporates, minerals are left behind often forming salt lakes. If all the water evaporates you may have salt flats left behind.

Lakes on the other hand do have river(s) flowing out. They will usually have river(s) flowing in as well, but a lake can exist from just rain or glacial melt. In fact, they are often formed as glaciers melt or where rivers widen and slow. Of course, they are less common in arid regions.

Rivers flow from lakes and mountains where glacier melt or rainwater form a river. They run downhill wherever possible (otherwise you would have a lake or an inner sea). It is important to note that mountains can form divides of river networks. In other words, rivers from the top of the mountains that flow down on one side will stay on that side and join others on that side. And rivers that flow down the other side will join others on that side.

Rivers of course grow in size as they progress to the ocean or an inner sea. Rivers may also form gorges and valleys in other terrain as their erosion affects the terrain.

Remaining Terrain

With all of the above in mind, place your remaining terrain. Vegetation will develop where there is adequate water from rivers and moist air. So place forests and farmland in those areas. Arid winds can cause deserts. Areas downwind from mountains may be rocky badlands or barren hills to start, then lead to grasslands before the air may have enough moisture to support more vegetation. Swamps and marshes will be located in low areas with plenty of water such as near coasts or an especially slow section of a river.

Remember the climate will affect the terrain you place. A forest in a subarctic region should be evergreen, for example.

Refine the terrain as you add other things to the map. Placing a new river may prompt you to add some forest or farmland. As you increase a forest you may want to change some of it to heavy forest.

It Is A Fantasy Map You’re Making

Keep in mind that you can throw out any of the rules above because “Magic”. The wizards might have created a lush paradise in the middle of what should be a desert. Or a god might have dropped a mountain down decimating the landscape of a region. It is often good to purposely put some fantastical things in your map. Let your players or readers know they are in a fantasy setting. But you can also use this to say “magic” to explain a mistake you notice later.

Finally

Building a world is a fun creative exercise, but you don’t have to do it all at once. Do the broad strokes of the world as you need to, or let Worldographer take the first stab if you’re using it. You can always change further away parts later–how accurate were world maps in the 1700s?

Then zero in on your campaign starting area and add detail to that region.

Thanks to The Worldbuilder’s Guidebook by Richard Baker that served as the basis for much of this article.